Monsters are a common theme in Medieval times, and show up frequently in the marginalia of the manuscripts. So here are two books that are about the monsters.

Medieval Monsters

By Damien Kempf & Maria L. Gilbert

Medieval Monsters has a brief description of what the monster was and gives an example of a medieval text in which the creature is described. It is a very much imaged based with the text taking up only a small part of the page (if at all).

The siren is a monster of strange fashion, for from the waste up, it is the most beautiful thing in the world, formed in the shape of a women. The rest of the body is like a fish or a bird. She sings so sweetly and beautifully that once sailors hear her song, they cannot resist going towards her. Entranced by the music, they fall asleep in their boat, and are killed by the siren before they can utter a cry.

The images aren’t referenced within the text, but there is a bibliography explaining which manuscripts were used for the book.

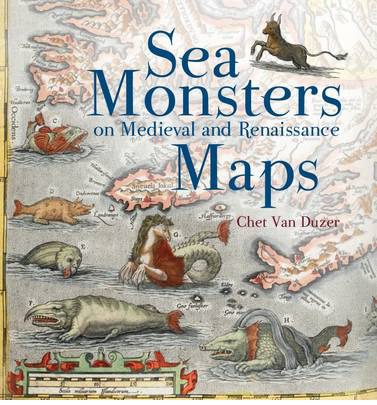

Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps

by Chet Van Duzer

Unlike Medieval Monsters, Sea Monsters is a lot more text based. Duzer is keen to describe in detail why monsters were on maps (and in some cases, why they were not) and to describe in far greater detail the history of the various monsters. He makes reference also to the various legends about the monsters and to the characteristics they were said to had. Not just monsters such as sirens, dragons and mermaids are described but also what we now know to be ordinary creatures were also sometimes described as monsters.

the arms of the polyp (octopus) are so strong it can pull a sailor form a ship into the sea and then eat him.

I would recommend Medieval Monsters to those interested in the images, and Sea Monsters for those who have more interest in the history, legends and more importantly, 10th-16th century mappaemundi.

[tabs] [tab title=”Medieval Monsters – Publishers Blurb”] From satyrs and sea creatures to griffins and dragons, monsters lay at the heart of the medieval world. Believed to dwell in exotic, remote areas, these inexplicable parts of God’s creation aroused fear, curiosity and wonder in equal measure. Powerfully captured in the illustrations of manuscripts, such as bestiaries, travel books and devotional works, they continue to delight audiences today with their vitality and humour. Medieval Monsters shows how strange creatures sparked artists’ imaginations to remarkable heights. Half-human hybrids of land and sea mingle with bewitching demons, blemmyae, cyclops and multi-headed beasts of nightmare and comic grotesques. Over 100 wondrous and terrifying images offer a fascinating insight into the medieval mind. [/tab]

[tab title=”Sea Monsters on Medieval and Renaissance Maps – Publishers Blurb”]The sea monsters on medieval and Renaissance maps, whether swimming vigorously, gambolling amid the waves, attacking ships, or simply displaying themselves for our appreciation, are one of the most visually engaging elements on these maps, and yet they have never been carefully studied. The subject is important not only in the history of cartography, art, and zoological illustration, but also in the history of the geography of the ‘marvellous’ and of western conceptions of the ocean. Moreover, the sea monsters depicted on maps can supply important insights into the sources, influences, and methods of the cartographers who drew or painted them. In this highly-illustrated book the author analyzes the most important examples of sea monsters on medieval and Renaissance maps produced in Europe, beginning with the earliest mappaemundi on which they appear in the tenth century and continuing to the end of the sixteenth century.[/tabs]